How WTA and public lands keep water clean for wildlife and people

60 million Americans rely on national forests for their drinking water. With that in mind, WTA builds trails that minimize impacts to waterways and can function as part of the surrounding landscape. We also advocate for land protections because protected and funded public lands mean clean water for people and wildlife.

Rainy fall hikes give us a chance to see something that trail crews think a lot about: how water moves on or around trails. Well-designed and well-maintained trails will be easy to travel, even if it's been raining for days. They are designed for water to flow so it doesn’t create problems for hikers (puddles to slog through) or for water quality (avoiding sensitive wetlands or soils).

You can hike along the Elwha River, which provides drinking water to the city of Port Angeles. Photo by Rebecca McCaffery, U.S. Geological Survey.

You can hike along the Elwha River, which provides drinking water to the city of Port Angeles. Photo by Rebecca McCaffery, U.S. Geological Survey.

“At the most fundamental level, a well-designed trail keeps water clean by allowing it to behave almost as though the trail wasn't there,” said Stasia Honnold, WTA’s southwest regional trails coordinator.

With trails working in tandem with the surrounding lands, landscapes can do what they are meant to: act as natural water filters.

Public lands are natural filters

Public lands keep water clean, filtering the water as it moves through plants and soils. By keeping landscapes and waterways intact, public lands provide clean water that wildlife and humans depend on.

National forests are the country’s largest source of municipal drinking water supply. For Washington and other western U.S. states, national forest lands are our main water source. Nationally, 60 million Americans rely on national forests for their drinking water.

Last month, WTA advocated to save the Roadless Rule for this very reason (among others). The Roadless Rule protects forests that provide clean drinking water and also outstanding opportunities to get outside. Over 3,900 hikers spoke up with WTA, and we’ll keep you posted on the next steps to defend this safeguard for our forests.

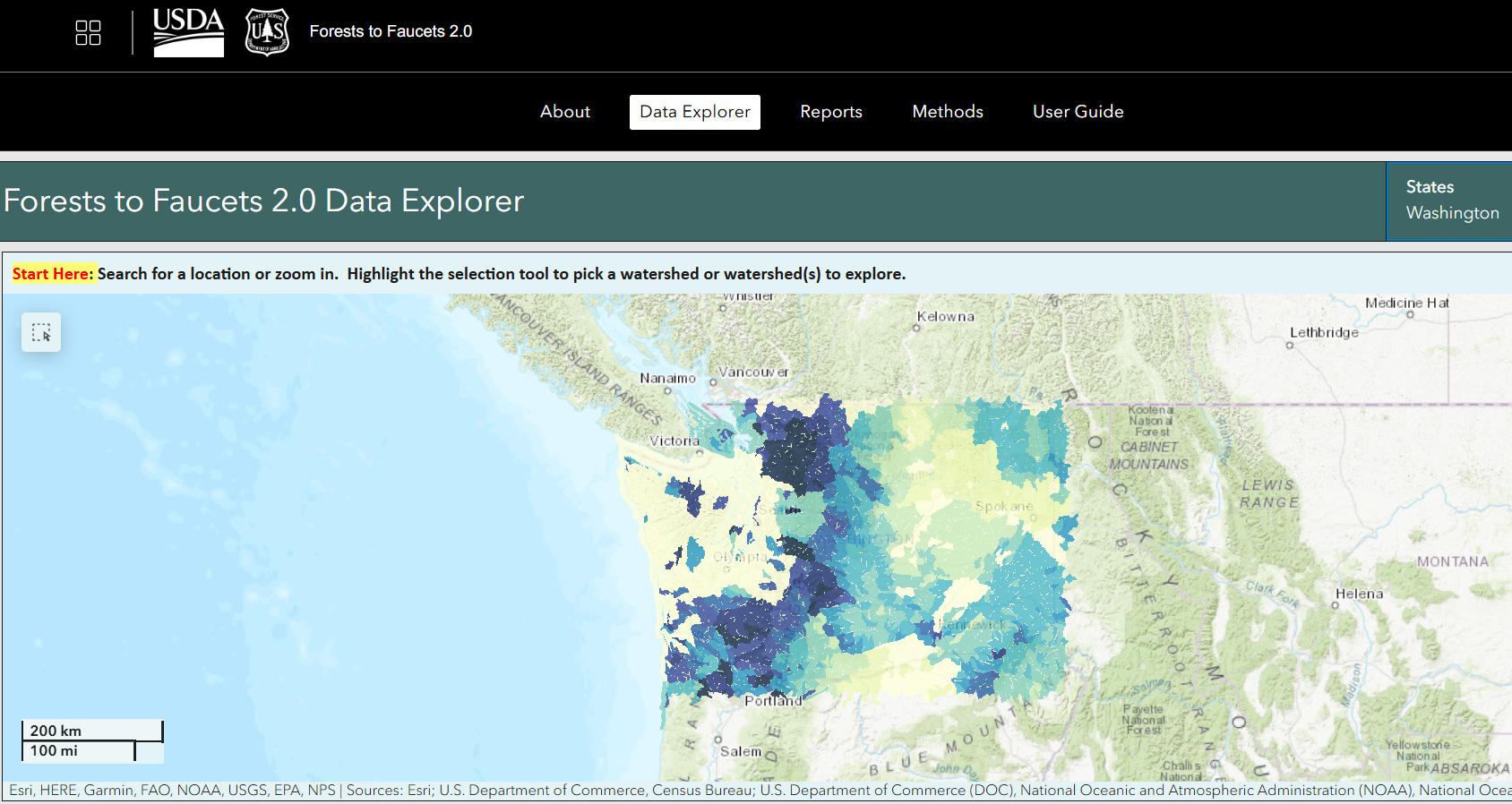

The U.S. Forest Service’s Forest to Faucets tool explores national forests that provide drinking water to 60 million Americans.

The U.S. Forest Service’s Forest to Faucets tool explores national forests that provide drinking water to 60 million Americans.

Olsen Creek: Building trails to keep Bellingham’s water safe

Alongside our advocacy, WTA’s trail work contributes to healthy public lands that keep water clean — from your backyard to the backcountry.

A great example is our recent work with Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and other partners to open official trails at Olsen Creek State Forest. Olsen Creek drains into Lake Whatcom, which is the city of Bellingham’s drinking water source. That means that water quality was a top priority for trail work on the lands surrounding Olsen Creek.

One of DNR’s goals in building trails at Olsen Creek was to improve the health of Lake Whatcom. By giving people trails to use, it will minimize people wandering beyond trails and causing erosion that could cause soil to wash down into the lake.

Water that flows into Lake Whatcom supplies drinking water to the city of Bellingham. Photo of Whatcom Falls by WTA trip reporter thebrink.

Water that flows into Lake Whatcom supplies drinking water to the city of Bellingham. Photo of Whatcom Falls by WTA trip reporter thebrink.

Another goal was to increase the miles of trail for people to enjoy. The team built new sections of trail and also moved and upgraded sections of user-built trails, routing them away from sensitive areas and using turnpikes to lift the trail out of wet spots. (More on turnpikes below.)

The trail work process was also conducted with the goal of clean water in mind. Trail crews placed silt fences and straw structures in drainages to keep water clean during construction. Crews only had a 4-month window when most trail work is allowed in the area. That made DNR’s partnership with WTA and other nonprofits all the more essential to get the work done quickly.

Shedroof Divide: Turnpikes stand the test of time

In the northeast corner of Washington, the Shedroof Divide trail follows a ridge with sweeping views of the Salmo-Priest Wilderness Area and the Selkirk mountains. On one side of the trail, the land drains into Sullivan Creek, and the other side of the divide drops down into Idaho.

This summer, WTA’s Lost Trails Found crew worked to rebuild turnpikes on the Shedroof Divide trail. Turnpikes are trail structures that raise the level of the trail. They use two logs, or a series of rocks, that run along the sides of the trail. Within that structure, you can fill the space in between, creating a trail surface that is higher than it was before.

WTA crew builds turnpikes to raise Shedroof Divide trail out of the mud, helping hikers and water quality. Photo by Andrew Zimmerman.

WTA crew builds turnpikes to raise Shedroof Divide trail out of the mud, helping hikers and water quality. Photo by Andrew Zimmerman.

On trails like the Shedroof Divide that travel near wetlands, turnpikes keep trails up and out of the mud. This makes it easier for you to hike and also benefits water quality. Turnpikes reduce the amount of sediment that washes from the trail into nearby waterways. They also encourage people to stick to the trail, instead of venturing off-trail to avoid wet spots. (Though WTA hikers know that muddy boots are better than trampled plants, and they stay on trail).

In July, WTA’s Lost Trails Found crew spent 288 hours rebuilding turnpikes on the Shedroof Divide trail to improve the hiking experience and protect surrounding water years into the future. For turnpikes that are made completely of rock and gravel, they can last for decades!

Our work protects lands and waters

WTA knows that the benefits our public lands provide spread far beyond the people who visit them. Water that flows through our national and state forests ends up in people’s faucets.

With that in mind, we build trails that minimize impacts to waterways and can function as part of the surrounding landscape. We also advocate for land protections because protected and funded public lands mean clean water for all of us.

Comments