Washington Trails

Association

Washington Trails

Association

Trails for everyone, forever

A guide to hiking and exploring some of Washington’s most fascinating geology. By David Hale and Kelsey Vaughn

As a hiker in Washington, you have endless opportunities to see evidence of the massive geologic forces that have shaped the views from your favorite trails. The testaments of volcanism, tectonic collision or glacial carving are everywhere. Mount Rainier’s volcanic cone and the Olympic Mountains’ sawtooth silhouette show the power of plate tectonics. The graceful golden hills of the Palouse and U-shaped valleys of the Cascades show the history of glacial bulldozers carving rock. But those classic examples aren’t the only place to learn about Washington’s fascinating geological history. When we look closely, we can discover less obvious, but no less interesting, examples. And we can appreciate how fortunate we are to live in such a dynamic landscape.

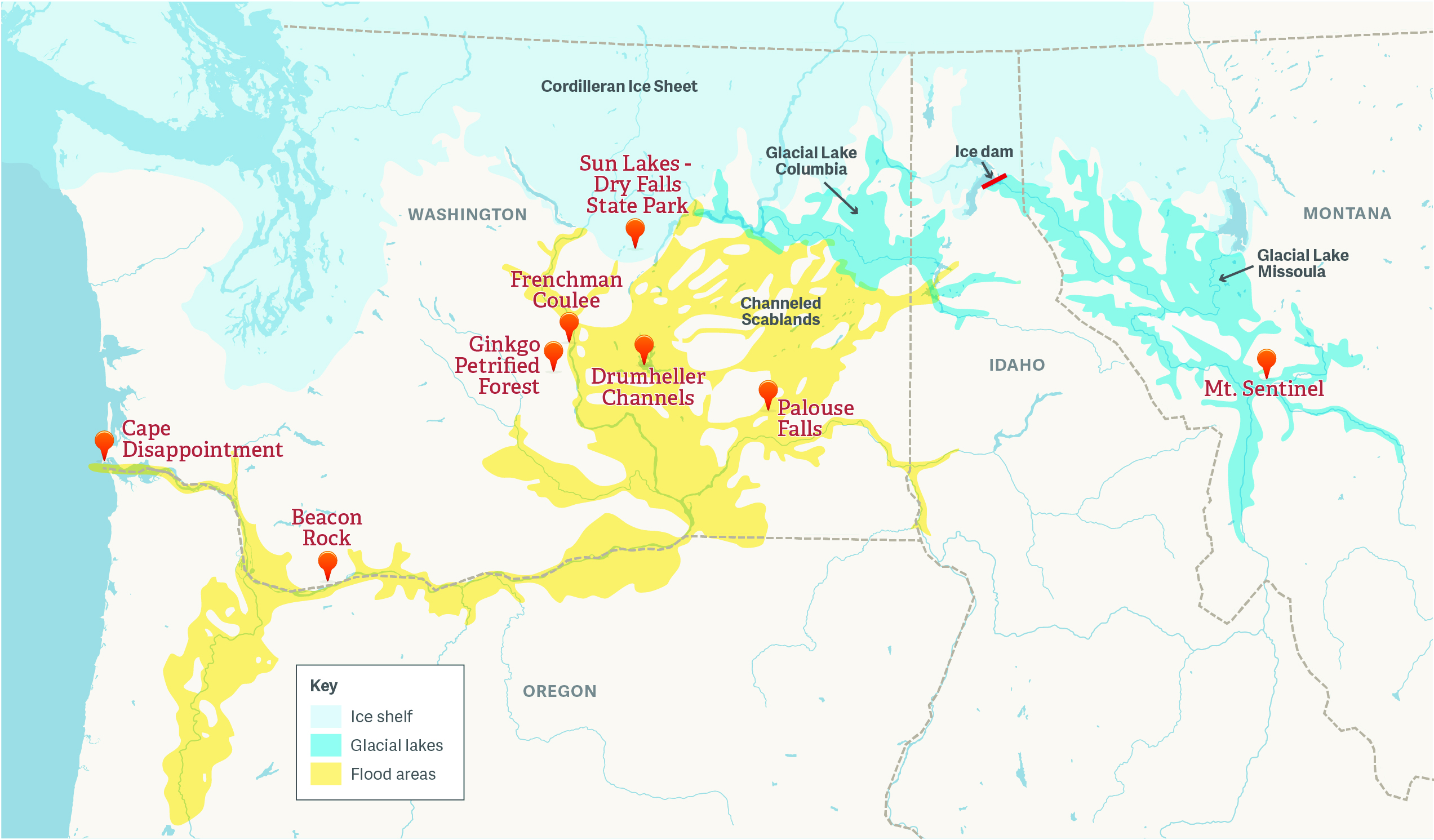

Washington's Ice Age floods map. By Lisa Holmes.

One of the powerful, but perhaps lesser-known, forces that shaped our state is surprising. There was once a waterfall in Washington state four times larger than Niagara Falls. It was 3.5 miles across, with a volume 10 times the combined flow of all the rivers of the Earth. The Dry Falls canyon that remains today is just one part of the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail — a unique trail you may not know about unless you are a fellow geology nerd. The “trail” is actually a set of national monuments, state parks and other points of interest that illustrate the impact of the Ice Age Floods on our landscapes. The trail starts in Montana and cuts a path across northern Idaho, parts of Oregon and Washington from Spokane to Cape Disappointment.

Recently, we visited many sites along this trail to see the incredible power of nature to form and re-form the landscape. We hiked in coulees, gorges and scablands that are evidence of a series of catastrophic floods between 12,000 and 18,000 years ago. We had seen many of these geologic features in the past, but knew little about their origin and the geologists who unlocked their mysteries. We’re sharing some of our favorite stops along the trail. Read the overview of the area’s geologic history (previous page). Then, with the stage set, let’s begin our tour of a few amazing places you can hike to read the stories our landscape tells about the mind-boggling scale of the floods.

The Ice Age Floods began when the ice dam holding back Glacial Lake Missoula began to fail, sending the first floodwaters into Eastern Washington. Desiring to see where it all started, we enjoyed a short but steep hike up Mount Sentinel to the “M” on the University of Montana campus. From this vantage point, we saw the “bathtub rings,” or strandlines, that mark the various shorelines of Glacial Lake Missoula. At its deepest, the lake is believed to have been approximately 2,000 feet deep. By comparison, Crater Lake is currently the deepest lake in the United States (and 11th in the world) at 1,943 feet deep.

While in the area: If you’re in Missoula in the summer heat, raft the Clark Fork River with a local outfitter. Back in town, you can stroll the “Hip Strip” across the river from downtown Missoula, where you’ll find independent boutique shops, cafes and restaurants.

From Missoula, the floodwaters roared west, carving channels across Eastern Washington and creating the barren landscape known as the channeled scablands. The jewel of the scablands is Dry Falls. After a beautiful drive along the canyons, we stood on a rock outcrop hundreds of feet above where that colossal waterfall once raged, envisioning a wall of water moving at 60 miles per hour, scouring out the 400-foot-deep chasm in front of us. The Dry Falls Visitor Center has an excellent exhibit about the Ice Age Floods and is worth a stop.

While in the area: If you go in the spring or early summer, try

hiking the Umatilla Rock Trail for up-close views of the desert landscape and rock formations. Or check out the potholes around Deep Lake. Spinning floodwaters, or kolks, removed chunks of basalt columns, leaving these distinctive potholes behind. Steamboat Rock State Park is also nearby and features a steep

hike with 650 feet of elevation gain.

Climbers scale basalt columns at Frenchman Coulee. Photo by Kelsey Vaughn, David Hale.

While we had “rocked out” at the Gorge Amphitheatre many times, we were really blown away by the scale of the show just a few miles away at Frenchman Coulee, off the Silica Road exit on I-90. Here, you’ll find towering basalt columns that the floodwaters eroded into a box-shaped valley, or coulee, for miles back from the Columbia River. The resulting landscape of gigantic exposed columns is a playground for rock climbers. We intended to hike down into the coulee to see the seasonal waterfall. Instead, we got drawn into the festival-like atmosphere and scrambled around watching the climbers.

While in the area: Cave B Estate Winery is only 8 miles away, next door to the Gorge Amphitheater. You can find wine by the glass and light snacks in its tasting room. Folks believe that the soil deposited by the floods is what gives Washington wines their amazing flavor.

Many large petrified trees are on display and found in situ at Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park. Photo by Kelsey Vaughn, David Hale.

Including this on the Ice Age Floods trail is a bit of a cheat. (The focus is not on the flood as much as what the flood exposed.) But we keep mentioning the basalt rock exposed by the floods, so we should explain where that basalt came from. Millions of years before the Ice Age Floods, hundreds of basalt lava flows were moving across Washington. We learned at the park’s interpretive center that petrified wood is not commonly found with basalt lava flows. But in this case, near Vantage, ancient forests were waterlogged and buried in mud when the flow arrived, protecting them from being destroyed by the molten lava. Instead, the lava encased the buried wood and the chemical processes of petrification began. Some of the petrified trees we saw while hiking on the Trees of Stone Interpretive Trail were exposed when the floods scoured away the overlying basalt. The park also offers an excellent viewpoint of the Columbia River Gorge.

While in the area: The Ginkgo Petrified Forest Interpretive Center, also in Vantage, has displays and a series of short films explaining the history of the petrified forest and how the Ice Age Floods shaped the landscape. Eight miles south of the park in Mattawa, the Wanapum Heritage Center (free admission) provides an opportunity to learn about the Wanapum people, their culture and traditions.

Beacon Rock is an old “volcanic neck” that was exposed by the Ice Age Floods. Photos by Kelsey Vaughn, David Hale.

We had previously visited this iconic spot on the Columbia River Gorge but didn’t know about its geologic backstory. On our most recent visit, as we scaled the 52 switchbacks on Beacon Rock, we now understood it was a “volcanic neck” — the core of an ancient volcano stripped bare by the floods. The trail leads to a spectacular view. From the top, we could see Bonneville Dam far below, which would have been under hundreds of feet of water at the time of the floods, nearly reaching where we stood 840 feet above.

While in the area: If you need provisions, just head a few miles down the road. From outdoor wear at the impeccably curated Out and About to craft beer and a hot pretzel at Walking Man Brewery, the small town of Stevenson has you covered. For more hiking, consider taking a stroll at St. Cloud day-use area, west of Beacon Rock. WTA has recently finished improvements to the trail there.

We covered a lot of ground on the Ice Age Floods Trail last year. Even so, three stops eluded us: Palouse Falls, Drumheller Channels and Cape Disappointment.

Palouse Falls is off the beaten path in Eastern Washington. The effort required to get there may be part of the appeal, and it’s the only remaining running waterfall from the flood path. Trails down into the canyon are permanently closed, but you’ll find several overlook spots accessible from Palouse Falls State Park.

Drumheller Channels is thought by some to be a quintessential stop to see stark evidence of the floods.

Cape Disappointment marks the spot where the floodwaters reached the Pacific Ocean, near Astoria. We plan to camp and explore the park’s 2 miles of saltwater shoreline, imagining when all that water finally rushed into the Pacific after traveling over 3,300 miles.

Washington State Parks has great campgrounds along the route for car and trailer/van camping.

• Riverside State Park

• Sun Lakes - Dry Falls State Park

• Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park

• Potholes State Park

• Palouse Falls State Park

• Beacon Rock State Park

• Cape Disappointment State Park